How Organisations create a culture of Leaning Forward

Organisations don't collaborate, people do. For collaboration to be of value it is necessary to build a culture of 'leaning forward': where people build strong relationships and trust, communicate meaningful information in a timely manner and anticipate how information and actions will impact on other members of the team and across teams within a whole community.

This is Part 2 of a series. See also Part 1 'Why it is important for individuals, teams and organisations to 'lean forward'.

The Organisation as a Community of Small Business

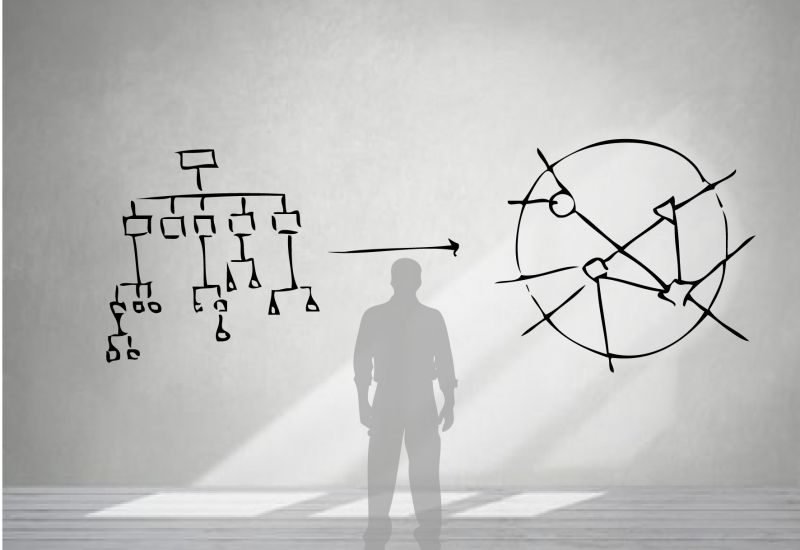

Organisations with traditional bureaucratic structures reinforce fragmentation and silos tend not to have a strong culture of leaning forward. Such organisations retain a command and control hierarchy, where information sharing is actively discouraged. A culture of leaning forward tends to be stronger in the presence of horizontally designed structures of small teams with a strong shared purpose, accountability and rewards.

To find great examples of such organisation we must look back to a pre-industrial age where organisations were communities of small businesses rather than the organised hierarchies most common today. One example are the communities of craftsmen who built the great Gothic cathedrals of the Middle Ages.

During medieval times, the Mastor Mason (aka architect) was the leader of a great number of craftsmen that were largely small family operations and members of craft guilds where skills were handed down from generation to generation. Each craftsman knew his trade and was respected by the other trades. Being a member of a guild meant that each craftsman was expected to uphold a code of ethics, maintain standards and mentor the next generation, in much the same way as professions do today. Often craftsman would follow the Master Mason from one project to another. The Master Mason knew these craftsmen, their strengths and their weaknesses and led them by defining a clear vision that they could share. Each craftsman was able to 'lean forward'; by anticipating consequences of their work on other trades and share the lessons learnt from past projects to collectively deliver an outcome that was up until that time considered impossible. The Master Mason was not afraid to call experts from neighbouring communities when they realised their ambition had outstripped their competence.

The resulting cathedral evolved and was the pride of a whole community.

As cathedrals took decades and often even centuries to complete, few people who worked on them expected to see them finished during their lifetimes. Being involved in the construction of a cathedral, even as the building patron, required a willingness to be part of a larger process.

The guilds of craftsmen disappeared during the industrial revolution despite attempts by enlightened entrepreneurs of the arts and crafts period to re-establish them. But from the guilds evolved the 'professions' as we know them today.

The power of communities of small self-organising teams is only just now beginning to be appreciated within larger organisations today, motivated by the increasing pace of change and uncertainty within commercial business environments.

For example, in May 2017, ANZ Bank in Australia announced it has adopted a similar playbook across its executive teams. CEO Shayne Elliot broke up the organisation into teams of 10 called squads, and groups of squads called tribes. It moved the organisation from the traditional command and control, risk based and process driven hierarchy to a purpose driven collaboration based communities that 'lean forward'. According to Elliot:

“This is about ownership: self-directed teams taking ownership and pride in what they are doing. This is about short time-frame delivery, it is not about delivery of things with a two or three year horizon. It is about getting things to market in about 6 to 10 weeks.” Says Elliot[1].

By flattening the hierarchy, empowering teams to make decisions, and strengthening horizontal connections, ANZ has set out to create a culture that is more resilient to change and more connected customers, collaborators and employees.

Other organisations are also following this trend, and in many ways this is a renaissance of the community of small businesses from the pre-industrial age.

Building Culture of 'Leaning Forward'

It is no longer enough for individuals to do one's job well. Individuals must 'lean forward' to collaborate, share information and anticipate the needs of others.

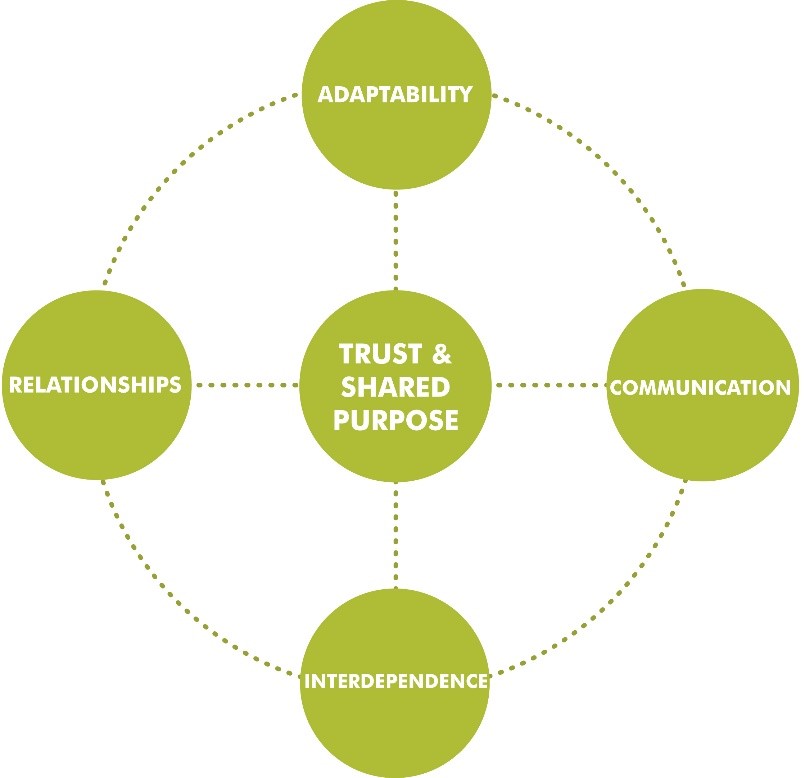

There are four dimensions to a culture of 'leaning forward' built around a core of trust and shared purpose: A relational dimension, a communication dimension, an interdependency dimension and an agility dimension.

The relational and communication dimensions were first described in the 1990's by Jody Hoffer Gittell and referred to as Relational Co-ordination: "High quality communication reinforced by relationships of shared goals, shared knowledge and mutual respect is pursued in tandem with process improvement to embed positive team behaviours and new ways of working together to achieve desired outcomes".

Today, as the quantity of information and the pace of change overwhelms us, two further dimensions are introduced: an agility dimension that is about monitoring and adapting to changes in the market and developing products rapidly, and an interdependence dimension that is about collating, interpreting, understanding and communicating the consequences of information on the whole community. John Dewar, Vice Chancellor of La Trobe University explains:

“We have a complicated operating model and it’s one that requires two things, it requires very clear accountability so people know exactly what their job is, but it also requires that if our people see a problem that isn’t their job to fix then they know where to go, whose job it is to fix it. So it requires deep accountability but great horizontal flexibility.”

The four dimensions of 'leaning forward' are set out below:

Relationships

- Connection between team members and across teams builds linkages across whole community.

- Generosity and Reciprocity is the currency of building strong relationships.

- Mutual respect and equality among those doing things.

Interdependency

- An understanding of the whole system and how each part contributes to the whole so that team members understand the impact of their work and information on other teams and the whole community.

- Interdependency often builds problems that can be resolved by collaborating together.

- Diversity and inclusiveness of viewpoints, mindsets, experience, ideas and expertise.

Adaptability

- Ability to respond rapidly to changing conditions and circumstances and source new skills and expertise when required.

- Flexible, and resilient to new information and customer preferences.

- Accepting of experimentation and failure, ability to learn and build upon mistakes.

- Ability to form new relationships and connections rapidly.

Communication

- Open systems build upon social systems and collective intelligence.

- Frequent communication to help build relationships.

- Timely information for work interdependencies.

- Accurate information to avoid error and wastage.

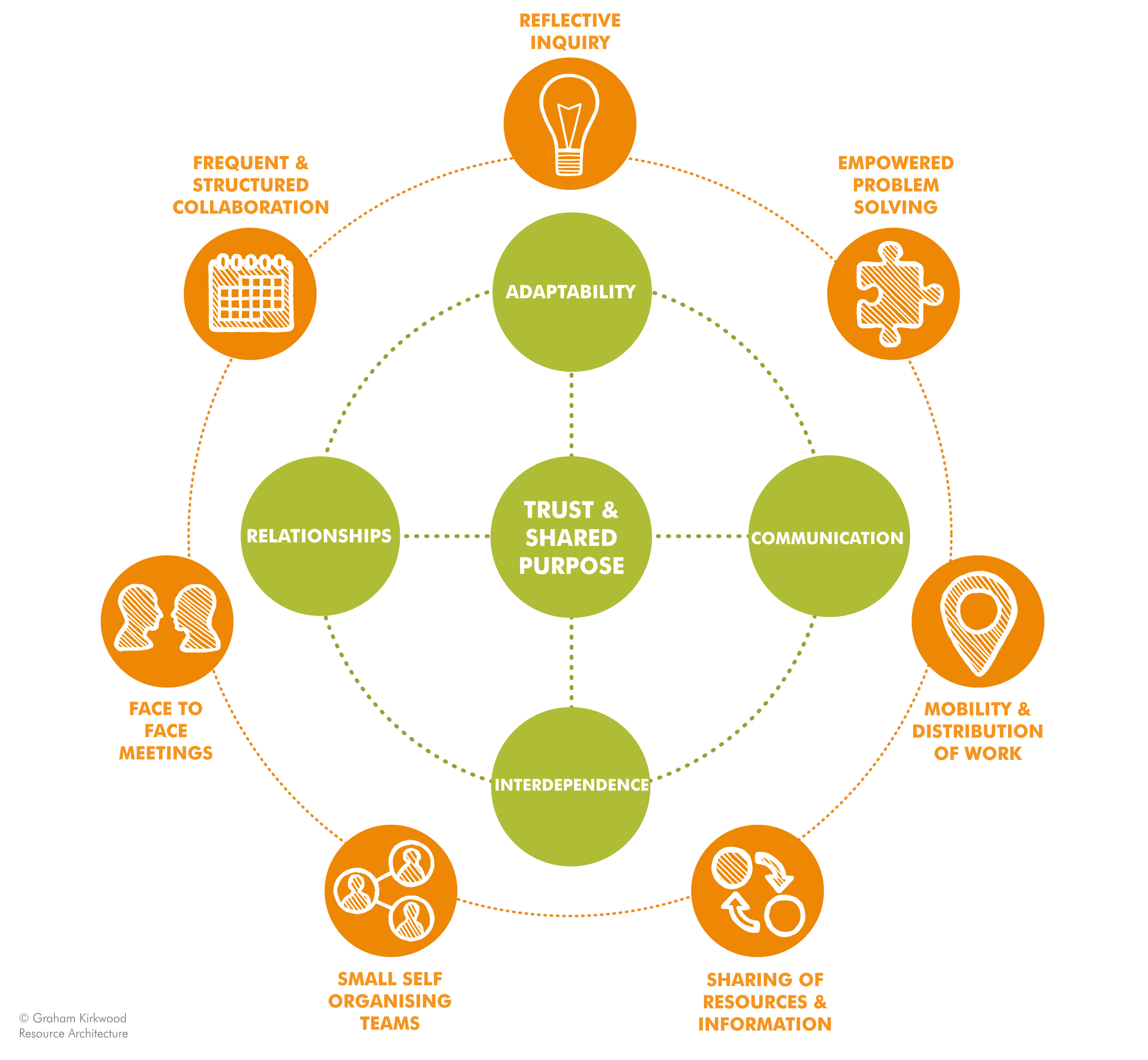

The 7 Behavioural Patterns of 'Leaning Forward'

As part of our work developing collaborative workplace strategies within the government and education sector, Resource Architecture has defined 7 workplace behavioural principles that support and reinforce the four dimensions of 'Leaning Forward':

Small Self Organising Teams

Research shows that an ideal work team is between 4 and 8 people and never more than 12. 4-8 is the number where each member can build a close working relationship and appreciate the diverse individual character strengths. It is also the accepted span control for any team leader.

Figure 2.6 Team Domain with variety of non-allocated work settings

Sharing of Resource and Information

Access to and reciprocity of information and resources is a central cornerstone in building trust and shared purpose. Examples include: Open systems that build upon digital document management systems and customer relationship management. Ability to embed collaborators and customers within a workspace for short periods.

Mobility and Distribution of Work

With new technology, people are less tethered to their desk and are able to maintain daily communications with their team, no matter where they are. Greater mobility and distribution of work enables team members to work alongside other collaborators, teams or customers.

Empowered Problem Solving

Enabling the team to solve problems at the source, rather than seeking executive authority, improves the quality and speed of decision making. For this to be effective each member must have a clear understanding of purpose in the context of the whole organisation. It also requires a higher level of connection with the customer.

Reflective Inquiry

Each individual and team require time for deep though and ongoing reflective practice. According to Systems psychodynamic consultant Nuala Dent. research shows that reflective inquiry, where individuals are given time and space to reflect and the team can talk together openly about their experience of work, enables a greater understanding of the team-as-a-whole and fosters collaboration and cooperation.

Frequent and Structured Collaboration

The more volatile the industry, the faster ideas and information flows better. But collaboration can be a milestone, unless it is structured and disciplined. Agile methodologies play a part in capturing and disseminating information more rapidly.

Figure 2.7 Team Scrum/Huddle for daily 15 minute stand up meetings

Face to Face Meetings

Face to face contact is what helps build trust and shared purpose. Social media, collaboration apps and emails, avoid face to face contact. With web conferencing, and greater mobility, people no longer have a reason not to engage others face to face.

The next article of this three part series will describe what work spaces and work tools enable teams to 'lean forward'.

[1] Australian Financial Review 2 May 2017 Page 1, ANZ Blows Up Bureaucracy